Medical Data Breaches: The Latest Health Care Epidemic

In recent years, there have been so many news stories about medical records being stolen that many patients now fear their confidential information is no longer safe. Those of us who work in the health care information technology arena are acutely aware of how severe the situation has become. A case in point: New York Presbyterian Hospital is among the many provider organizations that have experienced major medical data breaches. That incident was responsible for 6,800 patient records that became available to the general public on Google and led to a $4.8 million fine for the hospital.

Health care data, which can include a patient’s address, Social Security number, credit card information, health insurance information, and clinical facts about their diagnosis and treatment, has become an attractive prize for cyber thieves.

“While new health data is being created, stored and utilized on a daily basis, the security and protection of the data remains a chronic issue for the health care industry,” said HealthInformatics@GW Program Director Sam Hanna. “In order to achieve further adoption of new technologies and innovations in the areas of health informatics, the Internet of Things and predictive analytics, the health industry and all of its stakeholders must embrace a culture of security, privacy and data protection.”

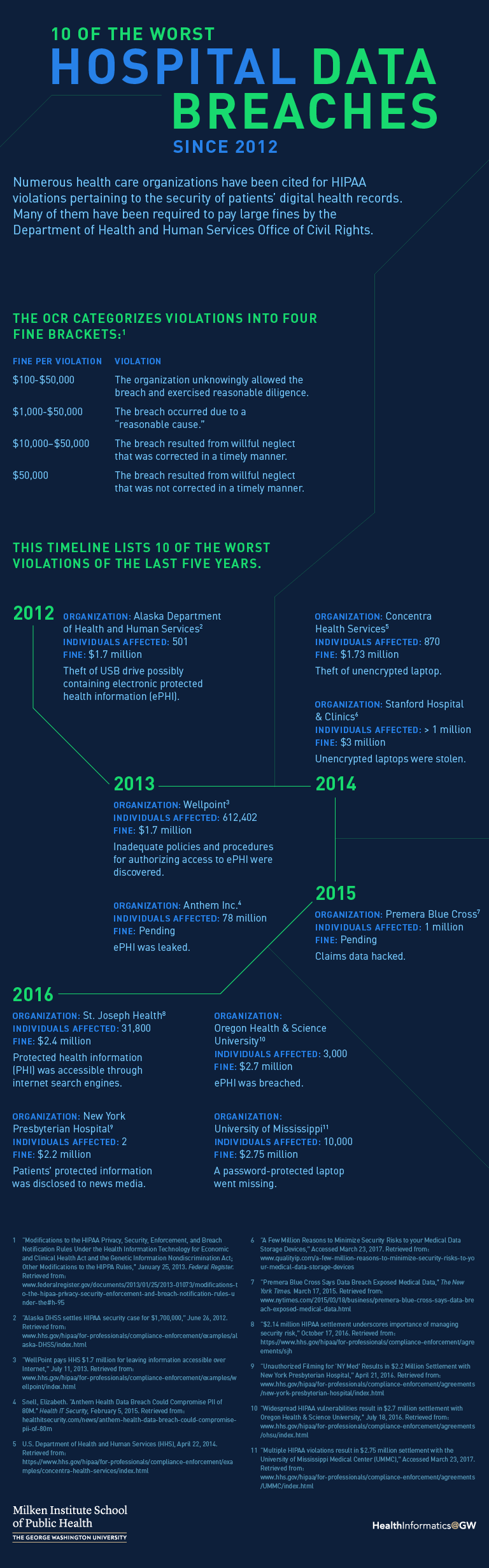

Go to a text version of 10 of the Worst Hospital Data Breaches Since 2012.

During cyberattacks, unauthorized people gain access to confidential information, referred to as protected health information (PHI), in a variety of ways. They may gain access by tricking an employee into revealing their password and then using their credentials to get into a medical office or hospital computer network. Another approach, called a phishing scam, deceives a staff member into thinking they are clicking on an email link that takes them to their favorite online store, for example. Instead they are sent to an infected website that downloads a virus or some other type of malware onto the practice’s network. The malware then gives the hacker access to PHI.

Health care data, which can include a patient’s address, social security number, credit card information, health insurance information, and clinical facts about their diagnosis and treatment, has become an attractive prize for cyber thieves.

Stolen PHI poses a different set of threats than personal information that’s taken from retail stores and other non-medical businesses. Having access to a patient’s insurance information and other medical data allows thieves to purchase expensive medical equipment, order prescription medication, or even pose as the patient to receive treatment, and then have the bill sent to the person who has been hacked. That doesn’t even take into account false charges on credit cards or damaged credit ratings. Breaches like this wreak havoc on an individual’s finances and personal life, usually costing many thousands of dollars to repair. Such breaches underscore that insecure health care systems can put thousands of patients at risk in one fell swoop.

Obeying HIPAA Rules

A 1996 law — the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act, or HIPAA — guides federal efforts to reduce the risk of health care data breaches. The Department of Health and Human Services issues HIPAA security and privacy rules that spell out what health care providers are expected to do to reduce the risk of PHI being compromised. Ignoring these regulations can result in large financial penalties for hospitals and medical practices and cause serious damage to their reputation.

HHS’ Office of Civil Rights (OCR) has been charged with monitoring providers’ adherence to HIPAA. It has created a website to alert the public to violations of the Privacy and Security Rules. Sometimes called the “Wall of Shame,” it lists over 1,000 providers that have experienced breaches,1 ranging from small providers to recognizable health care systems like Kaiser Permanente, Mount Sinai Medical Center and Anthem Blue Cross Blue Shield. While the portal doesn’t include details on the financial penalties, those figures are available elsewhere on the OCR site.

Investigation into a potential HIPAA violation typically begins when someone files a complaint with OCR. If the office uncovers a violation, it takes numerous factors into account when deciding whether to fine a provider and the amount of the penalty. While there is no simple formula, OCR considers how well prepared the organization was to ward off a breach in the first place: Did it perform a threat assessment? Did it train its employees to avoid common mistakes? Did it make a reasonable effort to safeguard PHI using physical and electronic measures?

More egregious violations incur larger penalties, which can run into millions of dollars.

Full details on the HIPAA Security Rule and how to comply with it are available in my book Protecting Patient Information.2 Essentially, the rule requires any organization that creates, manages or transports patient data to protect that information by putting in place a variety of physical and electronic safeguards. They include performing an extensive risk analysis to uncover potential weaknesses in its computer network, securing PHI on mobile devices, training employees and securing faxes that contain PHI. Providers are also expected to take reasonable precautions to protect paper records and must ensure that physical access to their computers is safeguarded.

Counting the Cost of Security — and Insecurity

One reason for data breaches is lack of understanding on the part of executives regarding the seriousness of the threat, which in turn results in their failure to allocate the financial resources needed to secure patient information. A survey of CEOs conducted by auditing firm KPMG, for instance, ranked the risks that they were most concerned about. Operational and regulatory risks topped the list at 47 percent and 36 percent, respectively. Information security was at the bottom of the list. Only 20 percent of the decision makers were most concerned about this threat.3

Many hospitals and medical practices believe it would cost far too much to make all the changes needed to fully protect patient data. So they may spend the bare minimum on anti-viral programs and memos to their staff about the need to “be careful” when online. That, coupled with the belief that “It will never happen to us,” has resulted in numerous security incidents.

When one compares the price tag for securing a provider’s computers and physical plant to the cost of having PHI compromised, it becomes clear that the cost of insecurity is too high. When one factors in HIPAA fines, which typically reach $100,000 or more, the cost of notifying all the patients who have had their medical identity stolen, the cost of providing each of them with crediting monitoring services, and the damage to the hospital’s reputation once the news gets out about the data breach, it’s usually less expensive to shore up digital defenses.

Taking Preventive Measures

Many providers open themselves up to the threat of a data breach by failing to do an initial risk analysis. The HIPAA Security Rule is very clear on this issue: “Conduct an accurate and thorough assessment of the potential risks and vulnerabilities to the confidentiality, integrity, and availability of electronic PHI (ePHI) held by the covered entity.”4

Go beyond a checklist: Providers need to realize that this analysis requires more than creating a simple checklist of security measures and ticking off each item as they put security measures in place. The Security Rule mandates an in-depth, formal process that is fully documented and safely saved. If a data breach occurs after an organization performs this kind of analysis and follows through on any vulnerabilities detected, it is likely auditors from the OCR will expect them to produce documents to prove that they have taken reasonable precautions to prevent the breach. A data breach in itself is not grounds for a fine or for listing an organization on the federal “Wall of Shame,” but if an organization can’t prove that it has evaluated its risks, the odds are not in its favor.

Inventory assets: One of the first steps in a risk analysis is inventorying all relevant assets. In other words, making a list of all the desktop computers, servers, laptops, tablets, thumb drives, CDs and smartphones that either store or have access to PHI. Then the organization will need to evaluate the vulnerabilities of each of these devices.

The federal government provides several useful tools to help providers perform a risk analysis and correct any problems it detects. For instance, the Office of the National Coordinator of Healthcare Information (ONC) provides an online security risk assessment app called SRA Tool, located on its website. Providers can download an executable file containing the program onto a Windows-based computer or iPad. The app will take users through a long list of questions that cover all aspects of security. This is a labor intensive process and will require many hours to complete; however, it helps providers review their password policies, the vulnerability of their smartphones, best practices for sending secure email, and the quality of their staff training efforts.

Invest in staff training: Staff training is an essential safeguard that reduces the likelihood of a data breach, and OCR expects providers to put a great deal of time and energy into this component of their security program; it is also covered in the SRA Tool. Staff training is so important because people are the weakest link in the chain. Phishing scams are the No. 1 reason that data breaches occur, so unless employees understand all the social engineering schemes that hackers use to trick them into opening infected hyperlinks, the organization remains at risk.5

Secure mobile devices: Unsecured mobile devices are another common reason for data breaches, and one of the most common reasons for providers to incur large HIPAA fines. While the HIPAA regulations do not explicitly state that mobile devices must be encrypted, if an unencrypted laptop or smartphone is lost or stolen and has PHI on it, the organization will be held accountable for the compromised data. In fact, the list of providers that have been fined because one of its unencrypted mobile devices was lost or stolen is quite long. Consider a few examples:2

- Concentra Health Services was fined more than $1.7 million because one of its facilities, the Springfield Missouri Physical Therapy Center, had an unencrypted laptop stolen.

- Adult & Pediatric Dermatology, P.C., a group practice, with offices in Massachusetts and New Hampshire, was cited by OCR because an unencrypted thumb drive containing the ePHI of approximately 2,200 individuals was stolen from the vehicle of one its staff members. The practice agreed to pay $150,000 for the violation.

- Seattle-based Providence Health & Services was fined for leaving backup tapes, optical disks, and laptops with unencrypted PHI unattended, which were then stolen.

Don’t Overlook Password Protection

Another way to reduce the risk of a data breach is to protect sensitive patient information by creating difficult-to-guess but easy-to-remember passwords. Many people use their pet’s name, their birthday, or some other common name or term. But hackers can use password cracking software programs to scan millions of common passwords per second, and these tools typically include every word in the dictionary, as well as expressions found in the popular and classical literature.

One way to avoid falling victim to these password cracking programs is to use a long random list of numbers and letters, for example “GjjkloiGl689Frlpw.” The problem with a password like this is no one can remember it. HHS offers a more practical solution in a PowerPoint slide presentation it created to help health care organizations train their employees to become more security conscious. The slides, which are located on the HHS website, provide several common sense suggestions:

It recommends that computer users create a password that is at least eight characters long and contains the following:

- A capital letter

- A lowercase letter

- A number

- A special character like %, #, *, or @

One way to create a strong password that is still easy to remember is to think of a short memorable sentence and then shorten it by using initials. For example, “You live at 345 Jefferson Street” could be shortened into the password: Yl@345JS. (Note that the upper and lower case characters match the upper and lower case letters in the sentence.) Of course, it would be wise to not use one’s current address to create the password, since that is often available on the Internet.

One way to create a strong password that is still easy to remember is to think of a short memorable sentence and then shorten it by using initials.

The theft of patient records has become big business, especially with the advent of Internet-connected electronic health records. Many health care providers still don’t realize how vulnerable they are to a data breach, or how expensive it can be to experience a breach. Many also don’t realize that a data breach that affects 500 or more patients will likely require them to notify not only the patients about the problem, but also the mass media. Once that happens, class-action lawsuits and a damaged reputation can get very expensive.

Putting in the time and resources to minimize the likelihood of a data breach is both the right thing to do and a savvy business decision.

References

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Office of Civil Rights. “Breaches Affecting 500 or More Individuals.” https://ocrportal.hhs.gov/ocr/breach/breach_report.jsf

- Cerrato, P. “Protecting Patient Information: A decision maker’s guide to risk, prevention, and damage control.” Elsevier/Syngress, 2016. https://www.amazon.com/Protecting-Patient-Information-Decision-Makers-Prevention/dp/012804392X

- “Global CEO Outlook 2015.” https://assets.kpmg.com/content/dam/kpmg/pdf/2015/08/global-ceo-outlook-2015.pdf

- Cornell University Law School Legal Information Institute. 45 CFR 164.308 – Administrative safeguards. https://www.law.cornell.edu/cfr/text/45/164.308

- “Is Your Organization Compromise Ready? 2016 Data Security Incident Response Report.” https://bakerlaw.com/files/uploads/Documents/Privacy/2016-Data-Security-Incident-Response-Report.pdf

Paul Cerrato, the author of Protecting Patient Information, has more than 30 years of experience working in health care and has written extensively on patient care, electronic health records, protected health information security, practice management and clinical decision support. He has served as Editor of InformationWeek Healthcare, Executive Editor of Contemporary OB/GYN, Senior Editor of RN and contributing writer/editor for the Yale University School of Medicine, the American Academy of Pediatrics, Information Week, Medscape, Healthcare Finance News, IMedicalapps.com and Medpage Today.