Colony Collapse, Climate Change and Public Health Explained

In early 2007, news broke that bees were disappearing as a result of colony collapse disorder (CCD), a phenomenon affecting the types of bees that live in hives — among them Apis mellifera, or the European honeybee.

CCD happens when the majority of worker bees in a colony disappear, leaving behind their queen, according to the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). Without workers, the hive cannot support itself, and any remaining bees eventually starve — a concern not only for the bees but also for the farmers depending on their pollination services and the people who rely on harvested crops for nourishment. In many ways, global food security and access to fresh produce hinges on the ecosystem supported by bees and other pollinators.

The EPA reports that cases of colony collapse have declined in the last five years. But CCD is just one kind of colony loss, and as global temperatures rise, bees will struggle even more to find nourishment and survive.

With an understanding of why colony loss happens and its implications for both public and environmental health, individuals can support the health of bees — and in turn, the health of their own communities.

A Brief History of Pollinators and Agriculture

Pollinators, such as bees, are critical to maintaining the global food supply. Through pollination, bees help produce the nutritious food created without the chemicals that could harm humans.

“Once we see die-off of beneficial insects [such as bees], we’ve got a real food production problem,” said Melissa Perry, ScD, MHS, professor and Chair in the Environmental and Occupational Health Department of the Milken Institute School of Public Health at the George Washington University.“It’s impossible to replace what we call the ‘ecosystem services’ of the insects and how they are pollinating the plants that we rely on for food.”

As reported by the Natural Resources Conservation Service of the United States Department of Agriculture, 35 percent of the world’s food crops rely on pollinators to reproduce, but climate change makes the pollinators’ plight more difficult. As temperatures rise and the earth gets drier, there is less nectar and pollen available for bees to use for honey, the bee’s main source of nutrients. When hives have less fuel, the bees have less energy for foraging and pollination dwindles. Without pollination, many crops can’t produce fruit.

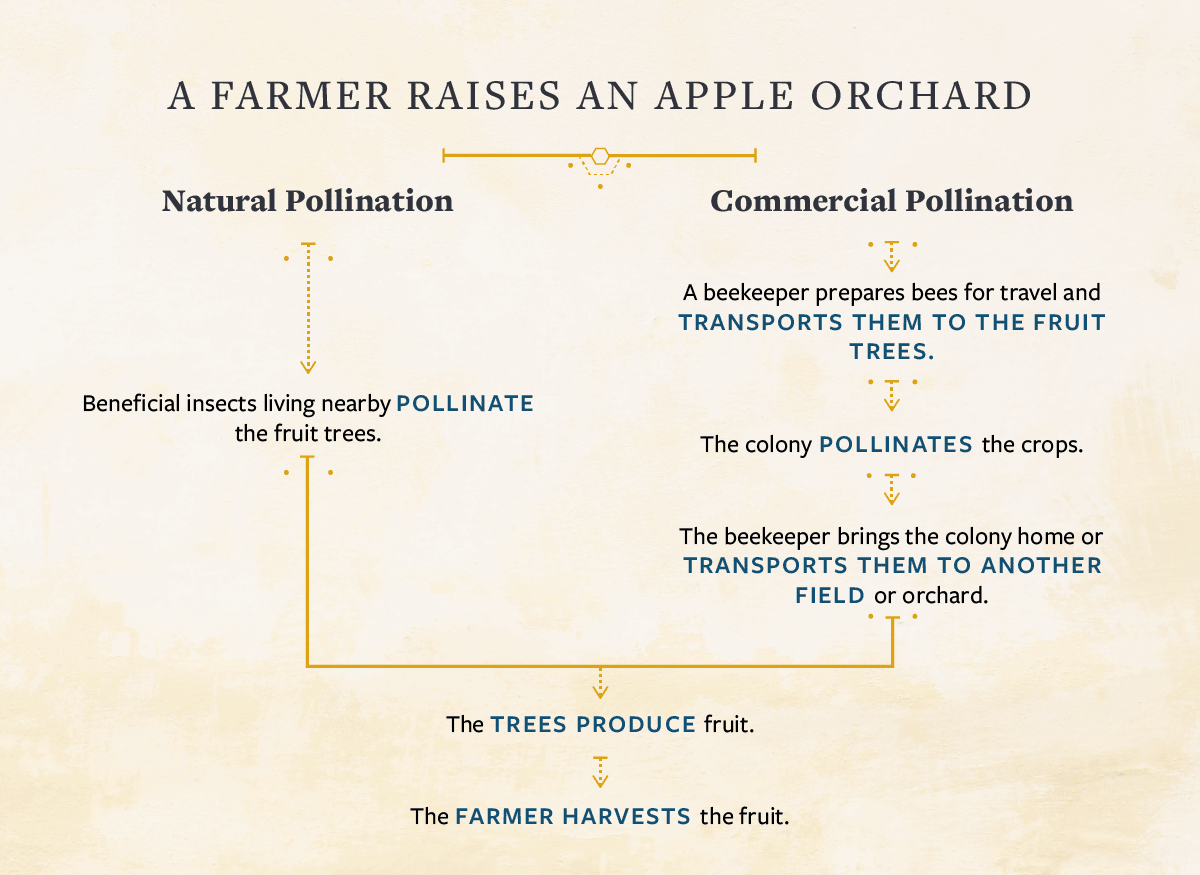

Today, much of modern agriculture relies on commercial pollination services to produce crops. Commercial pollination is a system developed to support the demand for food in a growing country. Farmers order colonies from beekeepers, who transport hives to the farmers’ land so that the bees can pollinate the crops.

Before commercial pollination, native insects — also called naturally occurring beneficial insects — did the pollination. However, pollinators died when farmers began using more pesticides to improve yield, said Perry. Many farmers and growers can no longer rely on their native services. Instead, they call commercial beekeepers.

Commercial pollination works well for farmers, growers and beekeepers, but the stress of travel and the chemicals used on the crops (the same chemicals that decimated the naturally occurring insects) can harm the bees. Ultimately, these colonies become less viable and food less secure.

Most experts believe multiple factors come together to cause bees to die and colonies to be lost, including pesticides, poor nutrition and mites. Individuals can support bee health and global food security by understanding and addressing these key types of stress.

FACTOR 1

Stress From Pesticides

Pesticide stress is thought to be a major cause of colony loss. Pesticides are biologically active substances designed to kill a specific target: worms, rodents, insects. Most of them cannot discriminate between the intended target and the beneficial insects — especially pollinators — that might also visit the plant.

Pesticides can be sprayed onto crops or applied to seeds, a systemic treatment that makes the entire plant toxic. A bee could come into contact with pesticides through the plant’s nectar or its guttation drops, a source of water for bees.

Pesticides work by attacking the nervous system. A large dose could kill the bee; sublethal doses just confuse the bee so much that it cannot find its way back to the hive.

“In general, bees are pretty wimpy against chemicals,” said Jay Evans, PhD, research leader at the Bee Research Laboratory of the U.S. Department of Agriculture. Exposure can cut a bee’s lifespan in half and lowers their immune response. With weakened immune systems, bees are less able to fight off the diseases they contract from neighboring mites. Furthermore, pesticides can destabilize a colony.

Solutions for Managing Pesticide Stress

People may not have much influence over farmers and growers, but they can take meaningful actions to reduce the amount of chemicals used in their own yards and communities.

Bee Health

Set up a birdbath.

Both birds and bees need water to survive. A birdbath can provide clean water that’s free of pesticides. This is especially important in areas that are becoming drier.

Environment

Question chemical use.

“Using chemicals is our reflex,” said Perry. “It’s our first impulse to say, ‘Well, let’s use a product to deal with a problem.’” But consider if chemicals are necessary in a given scenario: weeds on a lawn, roaches in the classroom, overgrowth in fields used for sporting events. Are there alternatives?

If you use a pesticide, follow the instructions.

Be sure to check the label for instructions about using pesticides, if you choose to use them. Only spray in the evenings, after bees have already returned to their hives.

Consumer Behavior

If you can afford it, choose organic.

Buying organic produce supports the farmers, growers and grocers working to make food without chemicals the norm. Pesticides can harm consumers of conventionally produced crops and the farmers as well. Some effects are relatively minor, such as nausea. Others are more serious, particularly for the individuals producing the crops. Comparing mortality rates among various occupational groups, farmers have higher rates of rare cancers such as non-Hodgkins lymphoma, said Perry.

Consult the Environmental Working Group’s (EWG) Shopper’s Guide to Pesticides in Produce.

Households trying to prioritize which organic is most important should review EWG’s lists of the Dirty Dozen and the Clean Fifteen (link below). It is still relatively safe, for example, to buy an avocado that isn’t organic because the fruit is protected by skin. But a strawberry with its skin exposed could have been directly sprayed with chemicals that have a cumulative effect on human and bee health.

FACTOR 2

Nutritional Stress

Another major contributor to bees dying is nutritional stress and starvation. This occurs either because the beekeeper fails to adequately replenish the hive’s food supply after removing honey, or because the bees were unable to store enough food before the blooming seasons ended. Microclimate changes, including hotter, drier summers, mean there is less forage and flowers for bees.

“[The colony] will sort of starve midwinter, in some cases, because they can’t collect new food in the winter. So, they fade away,” said Evans.

Even if the colony survives, the remaining worker bees have less energy for foraging and for providing for larvae, the future workers of the hive.

“Those first batches of bees they make are not nearly as healthy,” said Evans. That new generation, which should live for a month or more, falters. “They just don’t have it in them,” he said.

The absence of strong, healthy worker bees puts the entire colony at risk of collapsing or succumbing to pesticides or viruses. Evans and Perry recommend the following for reducing nutritional stress on bees in order to support the food chain.

Solutions for Reducing Nutritional Stress

As the climate warms and hot seasons lengthen, bee colonies will struggle to find adequate nutrition. Individuals can support colony health by providing homes and food for worker bees and advocating for more green spaces to incorporate flowering plants.

Bee Health

Provide nest sites for native bees.

Most native bee species do not live in colonies. Whereas honeybees lay eggs in hives, native bees build their own nests in the ground or in hollow trees, and they may have trouble finding natural nest sites after deforestation, wildfires and overdevelopment take a toll on the environment. Nest sites — bundles of straw with hollow stems or wooden blocks — can be hung under the eaves of a house or simply set outside.

Allow for white clover.

White clover is often considered a weed, but the flowers can be a source of food for bees. Consider keeping it wild, and avoid using chemicals to remove the plant.

Plant bee-friendly forage and flowers.

Not all flowers are good sources of nectar and pollen for bees. Find varieties that are, such as perennial shrubs, including hydrangeas and camellias. Cultivating plants that flower into the fall is especially beneficial for bees. “That’s what helps honeybees stock up for the winter,” Evans said.

Environment

Support your state government’s efforts to plant wildflowers.

Planting wildflowers instead of grass along roadways not only makes a drive more enjoyable but also provides habitats for pollinators. State departments of transportation typically run these “wildflower programs.” Write your state representatives to remind them why flowers are critical to both bee and human health and encourage them to support the program.

Encourage institutions to plant flowers instead of grass.

If your place of work or education is redesigning an outdoor space, contact the leadership to suggest planting a pollinator-friendly garden instead of grass. In schools, a garden can be educational for younger children learning about the natural world.

Consumer Behavior

Shop at quality plant nurseries.

Plant nurseries often have pollinator-friendly plant guides and staff who are knowledgeable about your area’s climate and soil quality. Ask for their recommendations, or check out Pollinator Partnership’s location-based ecoregional planting guides, Selecting Plants for Pollinators. (link below). Planning a garden can be fun for families and an opportunity to teach children about the connections between pollinator health and human health, as bees help create the flowers we enjoy and the food on our tables.

Recognize that environmental health is intertwined with insects and pollinators.

“We’re quite dependent on pollinators in order to maintain an abundant and healthy food supply,” said Perry. The extent to which the world’s nutrition depends on bees varies by report; the Natural Resources Conservation Service of the USDA claims around 35 percent of food crops need animal pollinators to reproduce. Protecting bees and other pollinators is, by extension, supporting global food security.

FACTOR 3

Mites and Disease

Others in the field, particularly pesticide companies, blame colony collapse on mites. A mite is an external parasite that latches on to a bee for sustenance. One particular kind of mite, the Varroa destructor, is infamous among beekeepers for eradicating colonies of honeybees in their apiaries, or collections of beehives.

Varroa mites feed on honeybees’ larvae, explained Samuel Ramsey, PhD, an entomologist with experience working at the USDA Bee Research Laboratory. On Bloomberg Environment’s The Business of Bees podcast, Ramsey described how these mites suck fluid from the larvae, infecting them with viruses. Once grown, these bees will be sicker and less effective as foragers. Rising temperatures already mean blooming plants are harder to locate; weaker bees will struggle even more to find food for the hive.

These mites also attack adult honeybees, transmitting diseases and feeding on their internal body fat. In particular, said Ramsey, mites feed on the bee tissue that detoxifies pesticides. The immune system is then compromised.

As a result, sick bees will commit “altruistic suicide,” voluntarily leaving the hive to avoid spreading illness to the other bees.

Solutions for Managing Pests and Disease

As the climate warms and hot seasons become longer and drier, bee colonies will struggle to find adequate nutrition. Individuals can better manage unwanted pests by prioritizing nonchemical treatments for bees and garden pests and supporting research labs that are developing new and safer methods.

Bee Health

For professional beekeepers, be careful with miticides.

A few miticides have been approved to treat varroa mites. Before using one, research its level of risk to bees, and be sure to follow the label’s instructions for treatment.

Consider natural options for treating mites first.

To avoid exacerbating bees’ stress, look into treatment options that don’t involve chemicals. Some beekeepers treat their hives with powdered sugar; you can find video tutorials online. Others recommend treating the hive with spearmint and lemon grass essential oils.

Seek advice from local beekeeping communities.

For hobby beekeepers, fellow bee enthusiasts in your area can provide helpful advice for hive care tailored to your specific location and climate. Try searching Bee Culture magazine’s Find a Local Beekeeper” page (link below).

Environment

For beekeepers, keep hives as far apart as possible.

One reason viruses spread quickly among honeybee colonies is that hives are placed too closely together — particularly those involved in commercial pollination. With limited land available for apiaries, spacing out hives may not be possible, but any distance could help.

To attack garden pests, start with the least poisonous strategy.

First, spray plants vigorously with water and pick the pests off. Next, try spraying them with dormant oils or insecticidal soap. You can mix your own insecticidal soap for garden pests using 1 tablespoon liquid dish soap (without bleach) per 1 quart of warm water, as suggested by Horticulture magazine.

Only use pesticides as a last resort.

Even as a last resort, try to use narrow-spectrum pesticides, which are designed to only kill the targeted organism. Avoid applying at times of the day when bees are flying; spraying in the evenings is ideal.

Consumer Behavior

Fund scientific research into bee health.

Consider financially supporting research in labs dedicated to improving bee health and studying the effects of mites. Findings from these groups can help inform new, more precise treatments.

Buy natural products for your own yard.

To manage pests in the yard or garden, choose products made without chemicals that could be toxic to beneficial insects. This can reduce the chemical stress on pollinators already burdened by mites, some so much they cannot move.

Recommendations for More Information

- Business of Bees: Invasion of the Beehive Bodysnatchers — Bloomberg Environment

- Mix Your Own Insecticidal Soap — Horticulture magazine

- Selecting Plants for Pollinators — Pollinator Partnership

- Find a Local Beekeeper — Bee Culture magazine

- Shopper’s Guide to Pesticides in Produce — Environmental Working Group

Citation for this content: MPH@GW, the George Washington University online Master of Public Health program