Global vigilance, and funds, needed to prevent pandemics

In July 2014, a businessman working for an international steel company took a flight from Liberia to Nigeria — and in that moment an already bad Ebola outbreak in West Africa threatened to become a worldwide catastrophe, the very stuff of Hollywood horror films.

The businessman felt feverish and sick on the plane. In the airport terminal he collapsed. He was taken to a hospital. No one knew it yet, but he had brought Ebola to Lagos, Nigeria, a megacity more than twice the size of New York City. A highly contagious pathogen set loose in a swarming metropolis with deep connections to the rest of the globe is what keeps public health officials awake at night.

Anne Schuchat, principal deputy director of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, was one of them.

She recalled how Nigeria, a poor country, was lucky to have the underpinnings of a good public health system thanks to national and international investments in the country’s polio eradication efforts. They knew what to do when the businessman tested positive for Ebola. The doctor in charge of Nigeria’s response had led the polio campaign. CDC-trained disease detectives tracked down the stricken businessman’s contacts. Fellow passengers on the plane. Emergency staff at the airport. Nurses and doctors. Quickly, others got sick. The outbreak spread. More disease detectives fanned out. In the end, they made 20,000 contacts. And 19 people died.

“But they stopped it,” Schuchat said during a March speech at the Kaiser Family Foundation about global health security risks.

The difficulty in stomping out this Ebola outbreak — after 12,000 deaths, almost entirely contained to West Africa — illustrates why so many public health officials are worried today by plans to slash funding for the U.S. government’s epidemic-fighting efforts. A new Ebola outbreak in the Democratic Republic of Congo that is believed to have killed more than 25 people since April, has only added to those worries.

Congress and President Trump are considering reducing funding by 60 to 80 percent for an ambitious program called the Global Health Security Agenda. The program, created just months before the Ebola outbreak exploded into view and funded by several wealthy countries, helps poorer nations with the prevention, detection and response to disease epidemics.

Already, the CDC is drawing up plans to stop its prevention work in 39 out of 49 countries. Other U.S. agencies involved in the initiative, such as the Agency for International Development and the Defense Department, would also be affected.

Public health officials who have helped design policies to facilitate coordinated responses to potential microbial outbreaks and pandemics point out that attention and funding often wane once an epidemic is over. Preventing one health crisis does not provide a strong argument for preventing the next one.

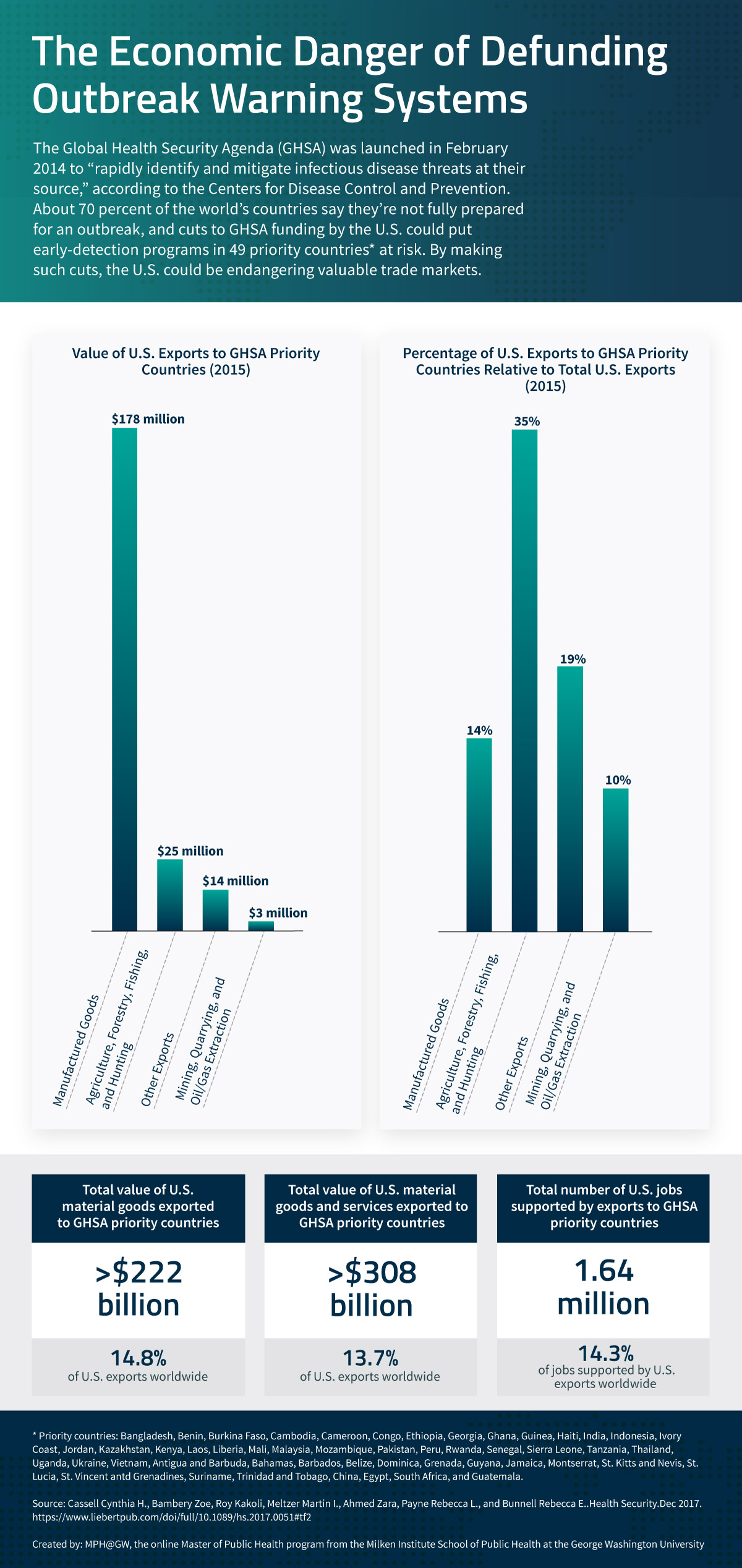

Go to a tabular version of The Economic Danger of Defunding Outbreak Warning Systems.

The desire to create the Global Health Security Initiative grew from watching countries struggle to implement the World Health Organization’s regulations for dealing with public health emergencies. About 80 percent of countries were not able to meet a 2012 deadline on the WHO guidelines. The initiative allows countries like the United States and South Korea to improve the public health infrastructure in far-flung countries — thus helping keep themselves safer, too — and creates a way to measure and track progress.

“It was seen as a way of getting countries to follow international health regulations,” said Ronald Waldman, a professor at George Washington University’s Milken Institute School of Public Health. “If every country is in a much stronger position, then we are all safer.”

Waldman warned it can be a tough sell.

“The question that comes up a lot is, why would a country, including our own, put money into preventing a future threat when there are so many more pressing problems?” Waldman said. “They see it as a zero-sum game with only so much money to go around.”

But global public health “is an issue that requires constant focus,” said Beth Cameron, vice president for global biological policy at the Nuclear Threat Initiative.

Cameron, who served as policy director for global health security on the National Security Council staff in the Obama administration, was one of the main architects of the Global Health Security Initiative. She said the program was created to combat the “cycle of panic and neglect” that typically follows disease outbreaks.

One of the agencies leading the global public health effort is the CDC. It focuses on four areas for the initiative: disease surveillance, laboratory systems, emergency operations centers and disease detectives.

Those came into play in April 2017, when it looked like Ebola had returned to Liberia. Several people had died after attending a funeral. That had been one of the main transmission routes in the outbreak three years earlier, discovered too late. But the country reacted differently this time.

A Peace Corps volunteer immediately phoned health officials in the capital, alerting them to the danger. The men on motorbikes who act as couriers for disease specimens notified health officials of a spike in activity. A disease detective rushed out and quickly ruled it was an outbreak of meningitis, not Ebola. A vaccination campaign was launched, helping limit the toll to 13 deaths.

“That was because of the investment in their public health capacity,” Schuchat said.

That work continues. The CDC is tracking 35 public health events considered to be “of international importance” across the world, such as a Lassa fever in West Africa.

“The fact that a deadly global pandemic has not occurred in recent history shouldn’t be mistaken for evidence that a deadly pandemic will not occur in the future.”

— Bill Gates

Foreign epidemics can have harsh economic consequences for the United States. A 2018 study in the journal Health Security estimated a widespread disease outbreak in Southeast Asia could cut demand for U.S. exports by up to $41 billion and put as many as 1.4 million U.S. jobs at risk.

The United States ships more than $308 billion of goods a year to 49 countries designated as global health security nations. A disease outbreak in one of these countries would be felt in the United States, according to a 2017 study, which “quantifies the extent of economic vulnerability to the US export economy posed by trade disruptions in these 49 countries.”

Countries dealing with epidemics also face economic pains. The 2014 Ebola epidemic brought the economies of the three nations hit hardest — Liberia, Sierra Leone and Guinea — to a standstill after years of rapid growth. The World Bank estimated the outbreak cost the nations $2.8 billion in lost production. The SARS outbreak in 2002-2003 hit Hong Kong and delivered “an unexpected negative shock” as local business dried up and tourists stayed home, in addition to having an estimated global economic impact of $40 billion.

Public health officials argue the Global Health Security Initiative needs funding to be prepared for when a truly worrisome disease outbreak occurs. They point out this is the 100th anniversary of the 1918 influenza pandemic, known as Spanish flu. It killed an estimated 20 million to 50 million people, including more than half a million Americans. More people died worldwide than in World War I.

“The conditions that created that pandemic are easily repeated and that would be a major, major blow and nothing could stop it,” Waldman said.

Bill Gates gave a speech last year at the Munich Security Conference warning that a global pandemic is one of the biggest threats faced by the world, right up there with nuclear war and climate change.

“The fact that a deadly global pandemic has not occurred in recent history shouldn’t be mistaken for evidence that a deadly pandemic will not occur in the future,” Gates said.

That message was reflected in a new listing on the WHO’s updated list of “priority diseases.” There was the usual lineup of horrible afflictions, including Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever, Ebola and Zika.

The new one went by the ominous “Disease X” — a placeholder name for the coming outbreak public health officials can’t predict.

Citation for this content: MPH@GW, the online MPH program from the Milken Institute School of Public Health at the George Washington University.