Are U.S. Cities Prepared for the Effects of Climate Change?

“Often we think about climate change as a temporally and spatially distant phenomenon, something that doesn’t affect me. It’s not going to affect me in my lifetime, or maybe not in the next 10 years or at least the next 20 years. Not at least until I’m old. But that’s not true. That’s not true here in the United States. That’s not true in other countries. We are already seeing the impacts of climate change in many dimensions.” — Milken Institute School of Public Health Professor Sabrina McCormick

Increases in the global surface temperature are expected to continue for decades, regardless of the mitigation strategies we’re using to slow that process. The warming trend, in turn, contributes to the increasing frequency and severity of extreme weather events. As a result, adaptation and preparedness for extreme weather and other adverse events related to climate change are more important now than ever – but are U.S. cities ready?

How prepared are our cities?

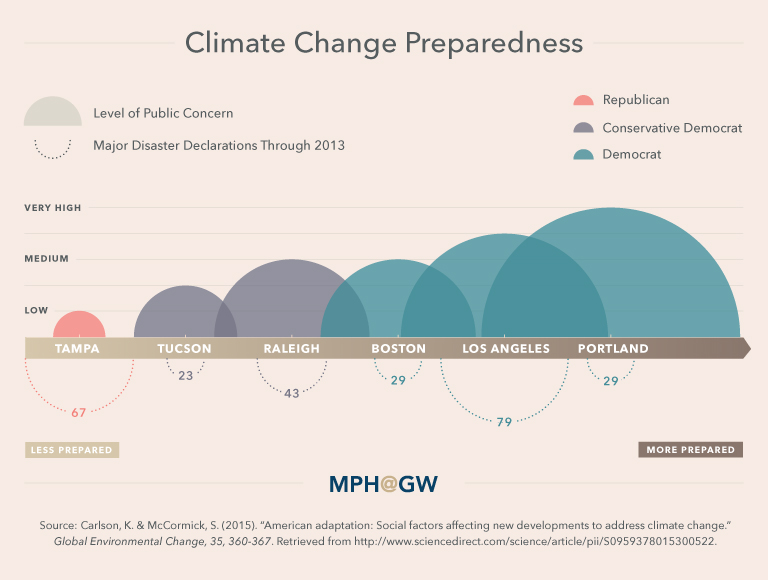

In the first of a three-part study on climate change, Sabrina McCormick, associate professor at the Milken Institute School of Public Health at the George Washington University, and Kathleen Carlson (an MPH student at Milken SPH at the time), conducted interviews with 65 local decision-makers in six major U.S. cities to find out how social factors influence whether U.S. cities are prepared for the consequences of climate change. McCormick found that Portland, Boston and Los Angeles were best prepared for the effects of climate change, while Raleigh, Tucson and Tampa lagged behind.

“I was inspired to do this study on how cities in the U.S. are being affected by climate change and how they’re preparing, or not, for those effects when I was working on a study with the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.” McCormick said.

What do the Terms “Adaptation” and “Mitigation” Mean?

Mitigation: refers to efforts to reduce or prevent emission of greenhouse gases.

Adaptation: seeks to lower the risks posed by the consequences of climate change.

“There was this kind of unwarranted assumption that cities in the United States are going to be fine in the face of climate change, and I thought we don’t really have the answer to that question — and we desperately need it.”

In the below visualization, we’ve illustrated some of the factors that influenced the six cities’ respective levels of preparedness.

Why focus on cities?

“Cities are a very important scale of study when it comes to climate change for a number of reasons,” McCormick said. “Eighty percent of the United States population already lives in cities, so it’s the vast majority of our population.” Furthermore, cities are at greater risk than rural areas because they contain areas of concentrated development and are populated by vulnerable groups.

Why focus on adaptation?

Many U.S. cities have planned and undertaken climate mitigation actions (i.e., the reduction of greenhouse gases) and, according to McCormick, a “wide range” of cities has developed climate adaptation plans. However, few have institutionalized those adaptation plans.

What hinders cities’ ability to implement adaptation measures?

McCormick identifies a few things that have prevented adaptation in the cities studied. The vast majority of investment money goes toward researching climate change risks, and cities also have planning gaps. They fail to consider factors that are not related to the climate or lack the capital needed for effective adaptation. Overall, though, research is limited on why adaptation is underway in some places and not others.

What do adaptation measures entail?

Adaptation measures, McCormick found, are often multidimensional and multisystem in nature. That means that various sectors, like transportation and energy, work together to prepare a city for the effects of extreme weather through land-use planning and emergency management.

Who was interviewed and why?

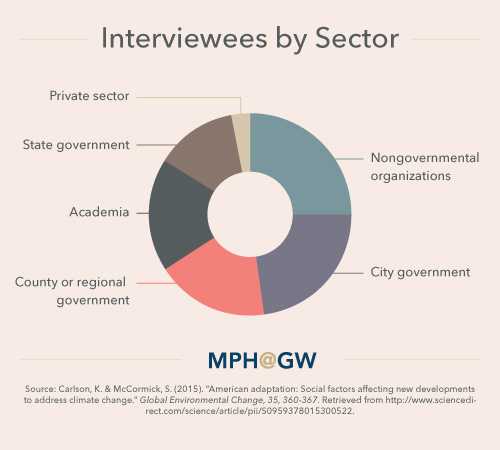

In-depth, semi-structured, qualitative interviews were conducted with 65 local decision-makers in the six major U.S. cities captured by the study. Most of these interviewees are from the public sector because “policy instruments are often critical to climate mitigation and resilience,” but a small percentage were from the private sector. Here’s the break down of interviewees:

How were interviewees selected?

The first set of interviewees was identified through a purposive sample, meaning that specific individuals (key local government officials and nongovernmental representatives involved in climate change or environmental planning) were asked for an interview. A second group was selected via a snowball sample, meaning that the interviewees from the first set were asked to identify subsequent interviewees with applicable backgrounds.https://www.youtube.com/embed//vex3MAoGh4o?enablejsapi=1

Why were cities ranked in this particular order?

The ranking is based on a qualitative assessment of climate mitigation and adaptation planning and implementation. Although several cities included in the study had taken steps to prevent or reduce greenhouse gases (mitigation), only three had taken specific measures to plan for the effects of damage that had already been done (adaptation).

How do social factors influence adaptation planning and implementation in the cities identified here?

McCormick and Carlson identified three categories of social factors that influenced cities’ preparedness:

Swing: Local events or characteristics that inspire or deter adaptation efforts.

- Political culture: In general, politically conservative areas are less likely than their liberal counterparts to support adaptation measures.

- Extreme weather events: For some cities, like Los Angeles, wildfires, droughts and even earthquakes have inspired adaptive measures. For others, like Tampa, similar threats of extreme events like hurricanes have become a normalized aspect of life rather than an impetus for change.

Inhibitors: Pre-existing ideological frameworks that hinder decision-makers’ ability and desire to promote adaptation.

- Scientific uncertainty about climate change: Decision-makers who don’t have access to scientific assessments outlining the impacts of climate change specific to their city are less inclined to prioritize adaptive measures.

- Politicization of climate change: Decision-makers who are uninformed about climate change – or deny its existence – are less likely to support adaptation.

Resource Catalysts: Types of information and moral grounding that provide a rationale for adaptation.

- Advocacy and political engagement: Communities that have a high level of interest and involvement in climate change issues can influence decision-makers in a way that encourages adaptive action and mitigation.

- Academic resources: Stronger connections between decision-makers and academic resources — local experts on climate change, universities and researcher centers — motivate the development of adaptive measures.

‘It’s not tomorrow. It’s today.’

When it comes to effecting meaningful change on an individual level, McCormick said that speaking up is key. “One of the findings in the study is that public engagement and civic advocacy really matter. So for individuals living in cities — really any city in the United States — if you’re concerned about climate change adaptation or mitigation, you should take action,” she said. “Particularly in light of this study, the action we would recommend would be engaging with your leaders, telling them what your concerns are, and asking them to take action themselves on a policy level.” Whatever the approach, however, that action must happen sooner rather than later. “It’s not tomorrow,” McCormick said. “It’s today.”

Source: Carlson, K. & McCormick, S. (2015). “American adaptation: Social factors affecting new developments to address climate change.” Global Environmental Change, 35, 360-367. Retrieved from http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0959378015300522